Inside the Vet World: What You Might Not Know About This Profession

Munirah Ahmad Niza

October 1, 2025

Veterinary medicine in Malaysia goes far beyond treating pets. Vets play vital roles in public health, research, education, and clinical practice. From government officers managing outbreaks, to researchers tackling antimicrobial resistance, to small-animal vets guiding families through tough moments, their work proves that this profession is as diverse as it is meaningful.

Beyond pets: Vets work in government, research, education, wildlife, livestock, and clinical practice.

Government vets: Protect public health, food safety, and manage outbreaks (e.g., Nipah virus).

Researcher/lecturer vets: Drive scientific breakthroughs and mentor the next generation of veterinarians.

Small-animal vets: Provide medical care for pets while supporting families emotionally.

Common traits across all paths: Compassion, resilience, adaptability, and dedication to animal and human health.

Growing need in Malaysia: With a national shortage of vets, career opportunities are expanding across multiple sectors.

When most people think of veterinarians, they picture someone in a clinic treating sick cats or dogs. But the truth is, this profession stretches far beyond the walls of a pet clinic.

Vets in Malaysia wear many hats, from safeguarding our food supply to researching the next breakthrough in animal health.

With pets now seen as family and livestock still powering much of our economy, the role of a vet is more critical than ever.

👉If you’re considering this path, check out our Veterinary Medicine Course Guide and our Veterinarian Career Guide!

Let’s step inside their world~

The Government Vet: Silent Guardians of Public Health & Food Safety

You may never meet a government vet, but their work touches your life every single day.

They’re on the frontlines of disease control, making sure threats like avian flu or foot-and-mouth disease don’t spiral into full-blown outbreaks, and are responsible for overseeing food safety and security by inspecting livestock.

Dr Maswati, Former Government Veterinarian

Dr Maswati’s love for animals began with her cats at home, sparking an interest in pursuing a degree in veterinary medicine.

While many imagine vets only treat pets, she discovered another side of the profession after graduating: protecting both animal and human health at a national scale.

Over the years, she has worn many hats as a government vet: lab researcher, state officer, animal industry developer, disease monitoring and even in managerial posts.

“Multidisciplinary skills are required because you’ll be expected to work in various fields. You’ll gain more skills and experience as you go through each posting,” she says. This versatility is what makes the role both challenging and rewarding.

But the weight of this responsibility is perhaps most visible during outbreaks.

She remembers the devastating Nipah virus epidemic: “Observing how the animals died during the fatal outbreak of the virus, and subsequently, the farmer of one of the visited farms also died due to the same virus.” This further highlights how closely animal health and human health are connected.

However, there are also many fulfilling moments for her in this profession. “I feel very fulfilled when I’m able to treat sick animals and see them recover completely, as well as supporting the animal industry in Malaysia through various means.”

Her advice for aspiring vets? To think bigger.

“Being a vet is not just about small animal practice. You can work in public health, research, livestock companies, wildlife, zoos or even as a consultant. It’s a field with endless opportunities.”

The Researcher & Lecturer Vet: Bridging Science and Students

Researchers investigate animal diseases, food safety, and even the sustainability of farming practices by publishing papers and contributing to solving outbreaks.

At the same time, as lecturers, they mentor the next generation of vets.

And while their work is less visible, the impact is equally significant in the industry.

Assoc. Prof. Dr Siti Zubaidah, Researcher/Lecturer Veterinarian

When Dr Siti Zubaidah was a child, her family had two cows. “I think they were my first pets and were the triggering moment that started my journey into vet medicine,” she recalls.

At the start of her career, she often encountered surprise, not for being a vet, but for being a woman treating large animals.

“My first case was a buffalo with a hernia. Due to the large size of the animal, maybe they [farmers] expected a male vet instead of a female vet. But after they saw how I worked and handled the animal, they trusted me,” she says with a laugh.

Now, as a lecturer and researcher at UPM, she balances teaching with investigating complex issues like antimicrobial resistance in dairy cows, a problem that affects both animals and humans.

“At the end of the day, our research helps farmers recognise problems that affect animal health and ultimately, the livestock industry. If we minimise these problems, we are indirectly contributing to food security for the country,” she says.

Despite the importance of her research, her greatest reward lies in teaching.

“It is very rewarding when you see your students understand how to apply your teaching in clinical medicine. It feels like I’ve contributed to something bigger when I see them carry that knowledge forward,” she says.

Her journey shows how vets don’t just treat animals, but also shape the future of the profession through education and research.

The Small-Animal Vet: A Lifeline for Pets and Families

This is the side of the profession most people know and love.

They handle everything from routine check-ups and vaccinations to life-saving surgeries and emergency care.

They are also a comfort to families, guiding them through challenging moments when pets fall sick.

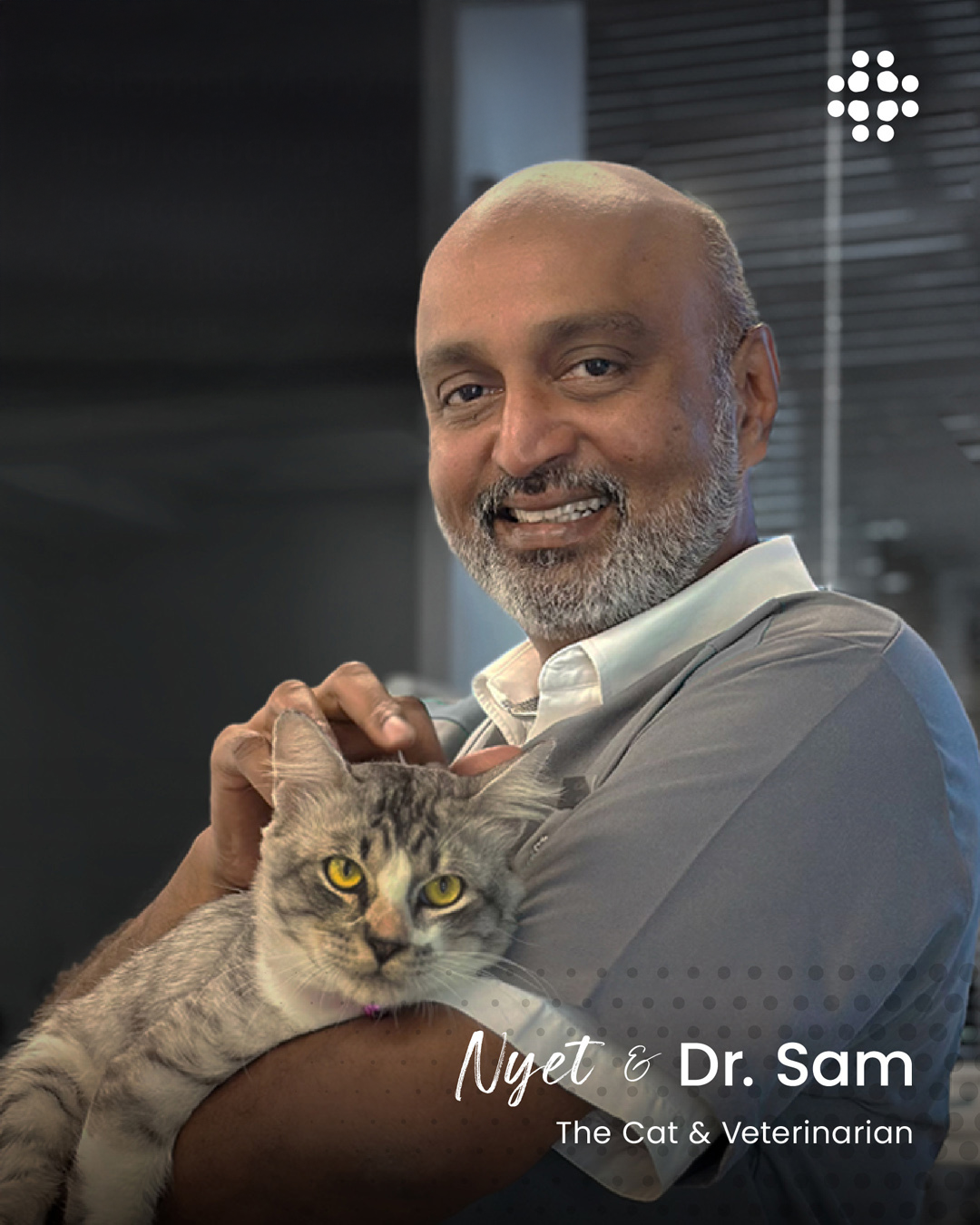

Dr Sam, Small-Animal Veterinarian

Dr Sam didn’t always plan to be a vet. Inspired by his parents, he first wanted to become an English teacher. But his passion for animals eventually led him to veterinary science, and today, he runs a small animal clinic in Penang.

However, running a clinic brings its own challenges. One of the biggest misconceptions he faces is about cost.

“People often think that because vets love animals, we should treat them with blood, sweat and tears without worrying about cost.” But as Dr Sam explains, there are real costs involved: diagnostic tests, X-rays, ultrasounds, equipment and expertise which come at a price.

The emotional toll is another reality few outside the profession truly grasp. “For many, pets are their children. So when we can’t save them, it’s very painful,” he says.

Yet Dr Sam stays grounded by reminding himself of the bigger picture: “We all want to heal every animal. But sometimes healing means letting go, and that’s one of the hardest truths of this profession.”

Dr Jason, Small-Animal Veterinarian

For Dr Jason, becoming a vet was straightforward; he loved animals. After five years of training in Indonesia, he returned to Malaysia to work in one of the busiest animal hospitals.

His daily routine is packed: morning check-ups, treatments, surgeries and consultations with pet owners. Most of his patients are cats and dogs, and every day brings something new.

One of his most memorable moments was with a Cocker Spaniel named Chino. “He wouldn’t eat until I bought him boiled chicken. Months later, when he saw me at a check-up, he started whining before I even reached him. That was really rewarding,” he recalls.

He also sees how quickly the industry is growing. “There’s definitely a shortage of vets right now. But the market is growing. If you’re passionate, it’s definitely a viable career.”

Dr Sharon, Small-Animal Veterinarian

Dr Sharon’s journey began with evenings watching National Geographic with her mother. She imagined she’d only be working with animals, not people. “But in small-animal practice, you also work closely with their owners,” she laughs.

After graduating, Dr Sharon was invited to work in the university’s small animal clinic. Initially, she had her heart set on radiology, but she embraced the opportunity and discovered her true passion. “I just love working with cats and dogs. My interest really grew from there.”

Over her 32-year career, she has learned to balance the emotional demands of the job with compassion and professionalism.

“When I’m treating my clients’ pets, they become my own. After so many years, I’m able to manage the sadness. But I always speak to the owners, comfort them and make them feel supported,” she explains.

Even after decades in the field, Dr Sharon still feels she’s exactly where she’s meant to be. “I can’t see myself as an accountant, a lawyer or even a medical doctor. This is where I belong. It hasn’t been easy, but I know I’m in the right place.”

A Profession Beyond the White Coat

From government officers safeguarding public health to lecturers shaping the future of veterinarians and small animal vets caring for your furbabies, the vet profession is far more versatile than meets the eye.

These stories show that being a vet isn’t just about treating animals. It’s about resilience, compassion, science and serving as a bridge between animals and the people who care for them.

And while Malaysia is still facing a shortage of vets, one thing is clear: this profession is growing, evolving and deeply rewarding. Their journeys are proof that veterinary medicine is not only a career, it’s a calling.